Chinese Raw Fish - 魚生 Yu Saang or 魚膾 Yu Kui

Currently, many younger Chinese people are not too interested in anything considered old or traditional. I think there are more American born Chinese who are more interested in these older traditional things out of a desire to reconnect with their mother culture. To me, tapping into something old doesn’t mean it has to be frozen in time. Small modern adjustments can also be introduced to keep anything feeling fresh, alive, and relevant. While I’m aware that in China, it’s still referred to 魚生 yu saang, I don’t think it would hurt to try and revive the ancient name for this which would be 魚膾 yu kui. (I’ve also come across a term that’s not as common which is 膾生 kui saang that refers to this dish, but for simplicity I won’t refer to this.)

I never thought I’d be making this dish, since this was only brought up in passing conversation with my parents when I was back at home and they’d occasionally buy sashimi or poke for me when I’d visit home. My parents generally don’t eat raw fish at all from a deeply held belief of a risk of getting worms from eating them and it’s not like it comes from nowhere. It turns out in Cantonese cuisine, there’s 魚生 yu saang which is translated just as raw fish. But there’s a preparation for this that appears to be unique.

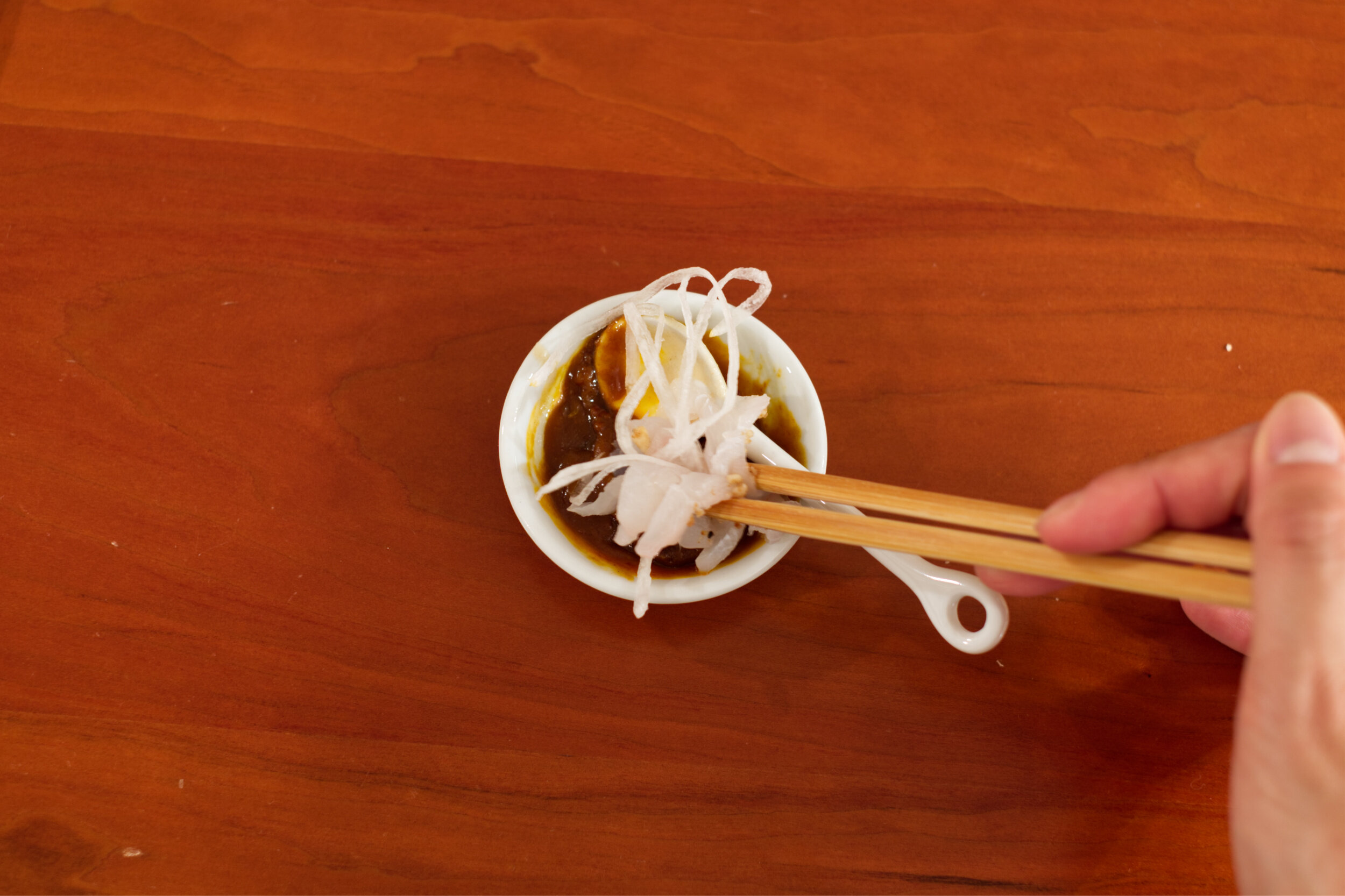

I recall my folks saying stuff about how they’ve seen the dish before, but never dared to eat it. Their description was that it’s raw fish that’s sliced thinly and you dip it in a sauce like sweetened soy sauce, with fried garlic and ginger oil, and green onions and cilantro. Years ago, one of my uncles who’s a professional cook, told me he ate it before as well. And before my uncle immigrated to America, he was a fishmonger in China so it made sense that he’d at least tried this before.

After doing some research on raw fish in Cantonese cuisine, it turns out that this could be a dish that somehow survived in the southern part of China, but was in existence for about 1500 years. There’s an ancient dish called 膾 kui that was popular and was first recorded in 禮記 The Book of Rites between 202 BC and 220 AD. At first, this dish was considered a dish for upper society and not exclusive to raw fish, but other types of raw meat. In the earliest forms, 鱠 also existed with a fish radical to specify that the dish was made with fish and 膾 was with other types of meat. While the word 膾 or 鱠 is no longer commonly used in China when referring to raw fish, they’re also the Hanja versions of 회, a raw fish dish in Korean cuisine. This is just shows how ancient raw fish is in both Chinese and Korean cuisines.

According to my parents, it’s rarely eaten in the north of China anymore, but it’s more known in southern China. While it’s not a common food, it’s not unheard of altogether.

As far as raw fish dishes exist for Chinese people, there’s one version that is associated with the New Year’s celebration and is found in Singapore and Malaysia. This is also called 魚生 yu saang , but not the version I’m going to focus on. If you’re curious about this version, Gold Thread did a pretty cool video about it.

The dish that I’m focusing on appears closely tied with the ancient dish. From old descriptions, even while it was eaten in north and central China, the fish that was used was some kind of 鯇魚 waan yu or grass carp and that’s the exact kind of fish my dad said that this dish is made with in Guangdong these days. It’s been known for a very long time that eating raw freshwater fish is risky because of waterborne bacteria as well as parasites are more common than in ocean fish.

I asked my dad why people would eat something like this if there’s a well known risk of getting a parasite of getting sick from it and he said that back when he grew up, times were tough and so you weren’t judgemental about what people ate to get by. But really, he said it’s for people who are just willing to take that risk because according to the people who do eat it, it’s really delicious. But he said that one thing that’s important with this dish is that it’s considered a drinking food. You have to drink strong liquor with it since there’s a belief (including the paired ingredients with the fish) that you’re introducing an antibacterial aspect of eating raw fish so you’re less likely to get sick or to catch parasites. I don’t think it works at all because of how fast you’re consuming this, but I think this belief has a big impact on how the dish has evolved along with the choice of ingredients to pair with it.

In ancient descriptions, there are mentions of sauces and how important they are to this dish. There’s an example from the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 AD – 589 AD) that specified a kind of sauce for this dish called 八和齑 baat wo jai that was made up of garlic, ginger, mandarian orange, white plum, cooked millet, cooked glutinous rice, and probably some kind of fermented soybean paste. It’s also no surprise from other descriptions that there are seasonal pairings where green onion is used in the spring and mustard seeds in the fall. It’s also now eaten where you mix in a variety of ingredients to complement the fish. The paired ingredients are vast and can include, but limited to, garlic, ginger, onions, green onions, shallots, cilantro, chili peppers, Sichuan peppercorn, makrut lime leaves, peanuts, fungi, fried shredded taro, fried vermicelli, sesame seeds, and more.

These preparations are really delicious and I think more should be eating raw seafood this way. It’s pretty exciting and the combinations are endless. Ika is really nice for this and it pairs really well with the two dipping sauces.

Recipe: *Listed below are the choices I made for this post and are reflected in the pictures.

Thinly sliced seafood of your choice, (pictured are ika, hirame, and kinmedai)

Daikon radish, thinly sliced

Sauces or assortment of mixing ingredients

Peanuts (optional)

Baijiu, whiskey, or mezcal (not pictured, but I drank a bunch of whiskey as I made this and also thought baijiu and mezcal can also go well with this, optional)

To prep the daikon radish, peel and thinly slice the daikon radish. Soak in cold water for about 10 minutes. Discard soaking water and repeat soaking with water once more. This helps reduce some of the spice from the radish and makes it sweeter tasting. Drain and set aside.

Optional: Lightly toast some peanuts and crush. Set aside.

To plate, add a bed of sliced daikon radish and top with the raw seafood of your choice. Sprinkle with toasted peanuts if desired.

Serve with sauces or mixing ingredients.

Garlic and ginger dipping sauce:

1/2 tbsp light soy sauce, adjust to taste

3/4 tbsp water, adjust to taste

1/2 tsp sugar, adjust to taste

Garlic

Ginger

Neutral Oil

Green Onions

Ginger

In a bowl, combine the light soy sauce, water, and sugar and adjust everything to taste. Since it’s raw fish, I try to make the sauce not so salty so the water and sugar is used to balance out the sauce.

Mince garlic and ginger and set aside. Heat a small pan over medium-low heat. When the pan is hot add enough oil to fry the garlic and ginger. Add the garlic and ginger and stir until it starts to turn golden. This can burn quickly so keep an eye on it. As soon as the garlic and ginger is fried to your preferred doneness, add the fried garlic, ginger, and aromatic oil to the soy sauce mixture.

Thinly cut green onions and roughly mince cilantro and add this to the sauce.

Dip any desired seafood in this. I think this sauce is the best all purpose one that can generally pair with most things as it’s not too strong tasting.

Soy sauce, sesame and chili paste:

Light soy sauce

Sesame paste (tahini)

Chili paste

In a small bowl, combine each of the three ingredients together to your preference. It will be different based on the quality/brand of light soy sauce you use as well as chili paste that you use too. For this, I used Caravelle’s Tia Chieu Sa-Te chili sauce and had ratio of roughly 1 part soy sauce, 1.5 part sesame paste, and 1 part Sa-Te chili sauce.

This sauce is really nice, but it’s a pretty strong tasting and would pair better with more fattier types of seafood or shellfish.

Assorted mixing ingredients:

Salt

Sugar

Sesame oil

Green onions

Shallots or onion

Cilantro

Garlic

Thai chili peppers

Ginger

Makrut lime leaves

Wash any herbs and thinly slice them and arrange them on a plate. If you are using shallots or onions, it is good to rinse them under cold water very briefly to cut some of the harshness of its spice.

Place salt, sugar, and sesame oil in separate dishes and serve.

From my research, there appears to be a specific order of how to put this together. First you put some seafood in a bowl, and mix salt, sugar, and sesame oil. Then you mix in other ingredients and the mixing helps release some aromatics from the herbs/spices. Last would be any fried ingredients to keep them from turning soggy.

This one can be the most light tasting so it can pair better with more delicate tasting seafood. But since this can have so many variations, this method can also be very all-purpose and ingredients can be picked or omitted to your preference too.